“Every second counts.” – The Bear, S2 Episode: “Forks”

Today’s class marked a critical shift in our lab work. Up until this point, we’ve been doing one-off techniques and dishes, with the most complicated recipe being a bruschetta. Today moved us into actual recipes using starches: Steamed Rice, Rice Pilaf, Whipped Potatoes, and Risotto.

I was excited about it all, but absolutely overjoyed at risotto. Dishes like risotto – technical, historical, impossible to find accurately prepared at a restaurant – was one of the reasons I signed up for culinary school. You can find dozens of online recipes, Youtube videos, opinions from celebrity chefs, detailing risotto and its proper technique. Culinary school introduced me to an instructor with decades of experience who learned risotto in Italy, and refused to compromise on any other definition or interpretation. We were learning real risotto. Period.

I spend a lot of time preparing for class, relishing the intellectual challenge of planning for ideal timing, perfect preparation, and the pathway to flavorful but simple dishes. I calculated the conversion rates (we scale back whole recipes for our individual practice) and wrote myself notes on techniques shown in the instructional videos. I befriended a lovely fellow student who strategized with me the day before. We both agreed rice, like eggs, were deceptively easy. People underestimated those tiny grains. They need attention, wisdom, confidence, and luck.

Being a student is one of the most difficult roles anyone can embody. It doesn’t matter what type of student. No one learning has it easy. If you’re struggling as a student, you feel disconnected and lost, watching everyone else’s back as they leave you behind. If you’re succeeding, confidence can start to get heavy, and the pressure to continue to succeed weighs around your neck as you try to keep your head up.

Before lab that day, Chef made a point to show the class my planning work, explaining how well I prepared and how the other students needed to step up their prep game. My heart sunk. The compliment from Chef faded away amid the white noise of memory. Being singled out for doing poorly feels horrible. Being singled out for doing well feels, in many ways, just as bad. My identity in class changed that day.

I’ve shared before how the class doesn’t really compete among themselves. No one throws elbows to get Chef’s attention. But we’re also all here because we want to be. The desire to do well, and get through the challenging physical hours of class, are intense. If one person was singled out for doing well, wouldn’t you ask them for help?

My meticulous preparation evaporated. Fellow students came up to me with questions, asking to see my work, wondering how I approached the conversions. None of their questions were rude or inappropriate. And I am good at setting boundaries. Repeatedly, I redirected questions to Chef. But, as someone with sensory issues, the interjection of my name quickly became grating. My concentration was broken again and again. I struggled to stay focused on the tasks at hand. More than that, my diligent preparation was still very much that of a student. It didn’t automatically translate into me actually knowing what I was doing. Most of the time, I had to respond to well-meaning inquiries with “I have no idea.”

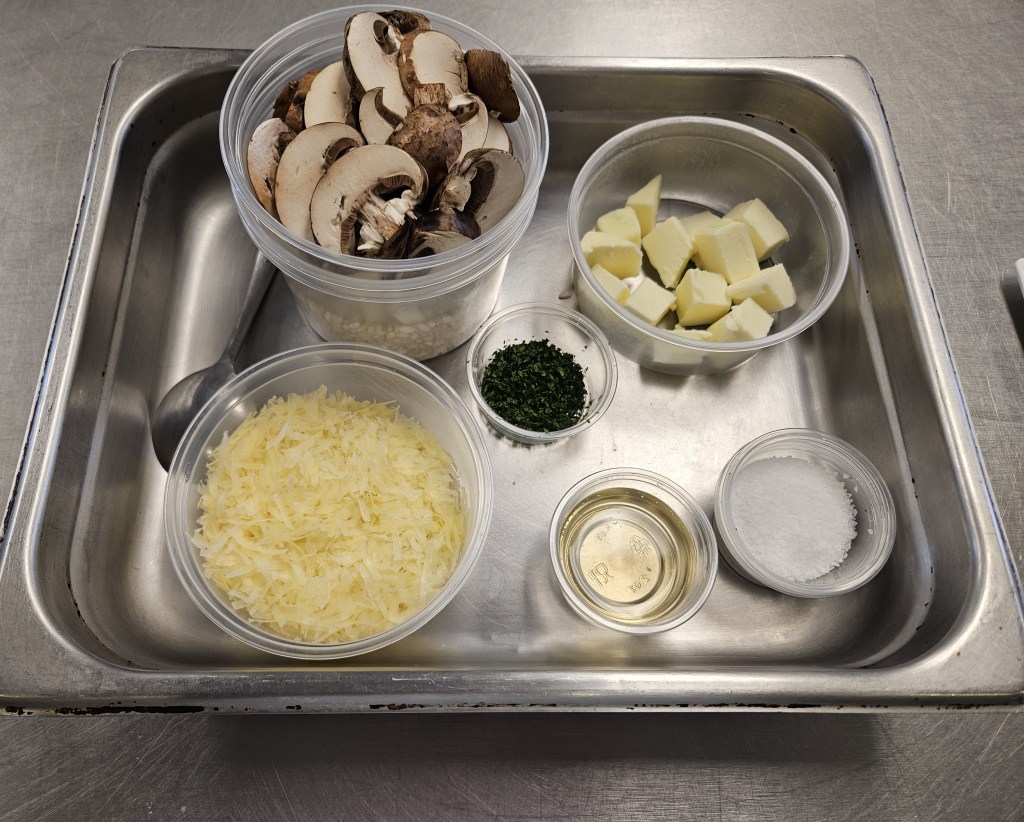

I knew going into this class that the most important dish for me to present to Chef was the risotto. I had practiced and studied, with no illusions that I would do well. I just wanted feedback. He had suggested to the class to start other dishes first and then get to the risotto. I blatantly ignored him, knowing it was likely a mistake. But the shift in class communication had me flustered, and, in my distraction, I let my mise en place slip. I wasn’t prepared for the dishes in the proper way and I saw quickly that my time was running out (again). This setback was different from tanking eggs over and over. This class was about rice and I was going to show nothing except risotto. I managed to prepare my mirepoix for rice pilaf. I threw hastily chopped potatoes into water. But the clock wasn’t lying. I was only going to be able to show risotto, so I just focused solely on that.

I ladled each portion of broth carefully, the grains not leaving my sight. I stirred and pushed and seasoned and tasted. I watched my potatoes sit in water waiting to boil. I saw my chopped vegetables sitting sadly in a bowl at my station. Somehow 45 minutes of risotto eclipsed the two and half hours I had to prepare. Overall, I fumbled. I couldn’t blame this one on a fancy flip. I had let the outside world in and lost my grip on the cook.

The one thing that kept my from tears was the review of my risotto. I had botched the plating, taking about 60 seconds longer than I had available. In that time, the delicate dish stiffened up. It was solid ont he plate, instead of beautifully lava-like. However, Chef declared the flavor immaculate, and said it was better than 90% of the risottos he had tasted in the state (though mine was quite stiff, like theirs). He even said that, as he watched me err in my plating, he saw that the product coming out of the pan looked great. “If you had plated it properly, it would have been great. Right now, it’s just good.”

You know what? I’ll take it.