“If you think you’re done, you’re only halfway there.” – Chef

The quote above was technically about chopping parsley, but I’m learning not to underestimate the universally applicable wisdom of simple cooking instructions. I tend to rush while cooking (an in life), a bad habit at home exacerbated by the stress of the kitchen lab. I always feel like the slowest, the last, that everyone else has landed on some sort of fast track to success. While its true that good things take time, its also true that things take time. So much of the technique I study in class is about when to move and when to wait. It makes a huge difference in the quality of food. Monitoring your time is also critical for staggering dishes in order to plate properly. This obstacle is one of the next to tackle in class. It’s been hard enough to plate two hot eggs onto a hot plate, but I’ll soon be asked to prepare full dishes like Eggs Benedict, with each item perfectly hot and delicious.

The foundation for creating a full and complete dish is sauce-making. Chef declared the next two weeks as critical not just for class but for our careers as potential chefs. Sauces are what separates a home cook from a chef. For many of us that cook at home, sauces are an afterthought. Maybe we do a quick deglaze after roasting meats and serve that with our entree. More often, sauces barely make an appearance in modern amateur recipes, only popping up after everything is complete, phrased in some vague way like: “Serve with pesto.” or “Drizzle with your favorite hot sauce!” For a chef, sauces are an integral part of the dish, as important as any other element, and are designed to complement and elevate eating. Texture, scent, viscosity, as well as taste, mean that a sauce is often that secret alchemical ingredient that elevates a plate from delicious to memorable.

Day One required the Mother Sauces: Bechamel, Velouté, Espagnole, and Tomato. We also did Mayonnaise, which isn’t technically one of the Mother Sauces, but Hollandaise was coming on Day Two and we needed to learn how to create emulsions by hand. These traditional sauces act as building blocks. Once you master them, you unlock a plethora of “Small Sauces,” and your sauce-making retinue grows exponentially. Essentially, liquid + thickening agent + seasoning = Mother Sauce. Mother Sauce + other whatnot = Small Sauce. Each Mother Sauce can be the foundation for dozens of other sauces. Basically, you just keep building and building until you get the flavor you want. It’s brilliant in how simple it is, each sauce branching out like the taxonomy of animals. From a primordial white roux comes an elegant Bechamel, then a cheesy Mornay…

First up, is the Bechamel. A white roux (lightly cooked flour and fat) with more milk, grated nutmeg, and an absolutely ridiculous-looking item called an onion pique (a bay leaf skewered on an onion with a few whole cloves). I was unconvinced of its culinary heft, but simmering it in the sauce infused a sort of “essence” of onion and spice. I usually don’t care for dairy-based sauces, but this one ended up being fragrant, flavorful, and somehow quite light despite being a rich sauce.

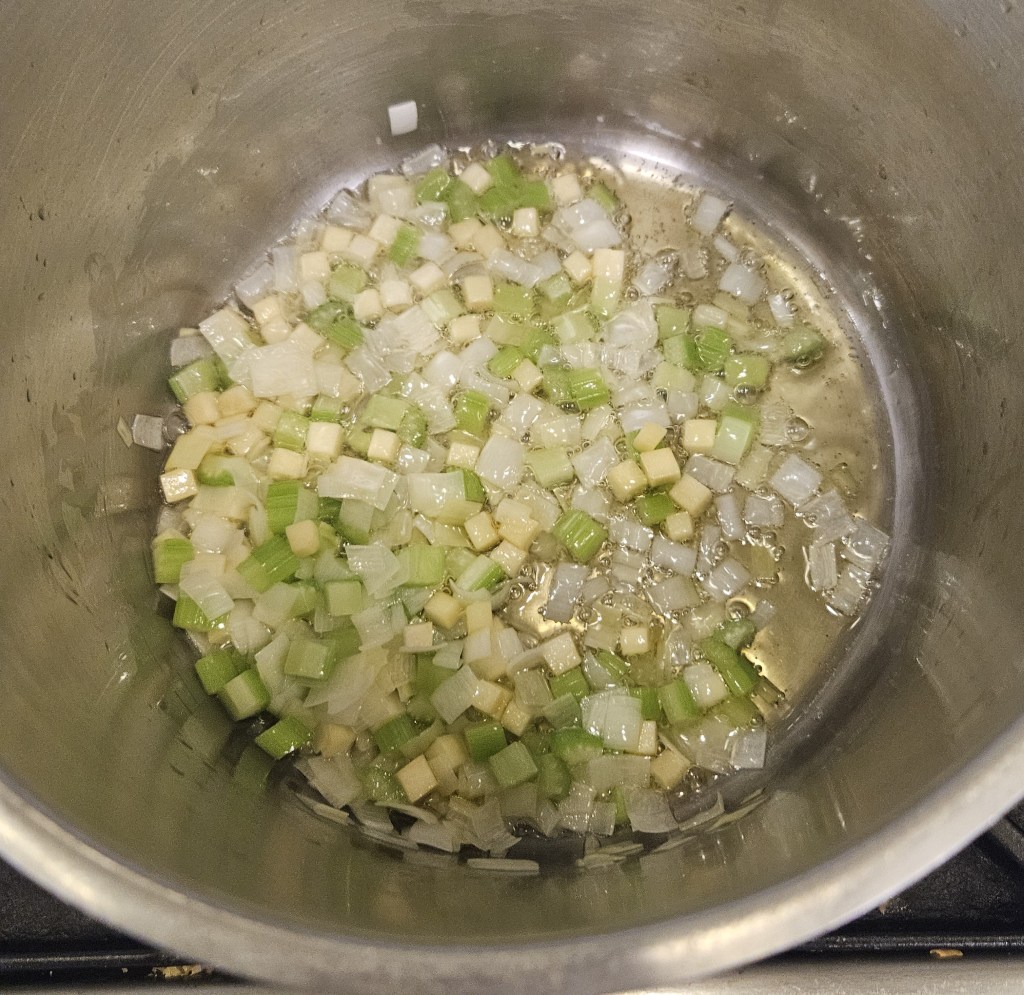

Next, we did a Velouté. A lighter mirepoix base (parsnips for carrots and leeks for celery) imparted similar flavors as a regular mirepoix, but kept the color of the sauce paler. Simmered with more herbs and stock, the flavor is like the greatest chicken noodle soup you’ve ever had.

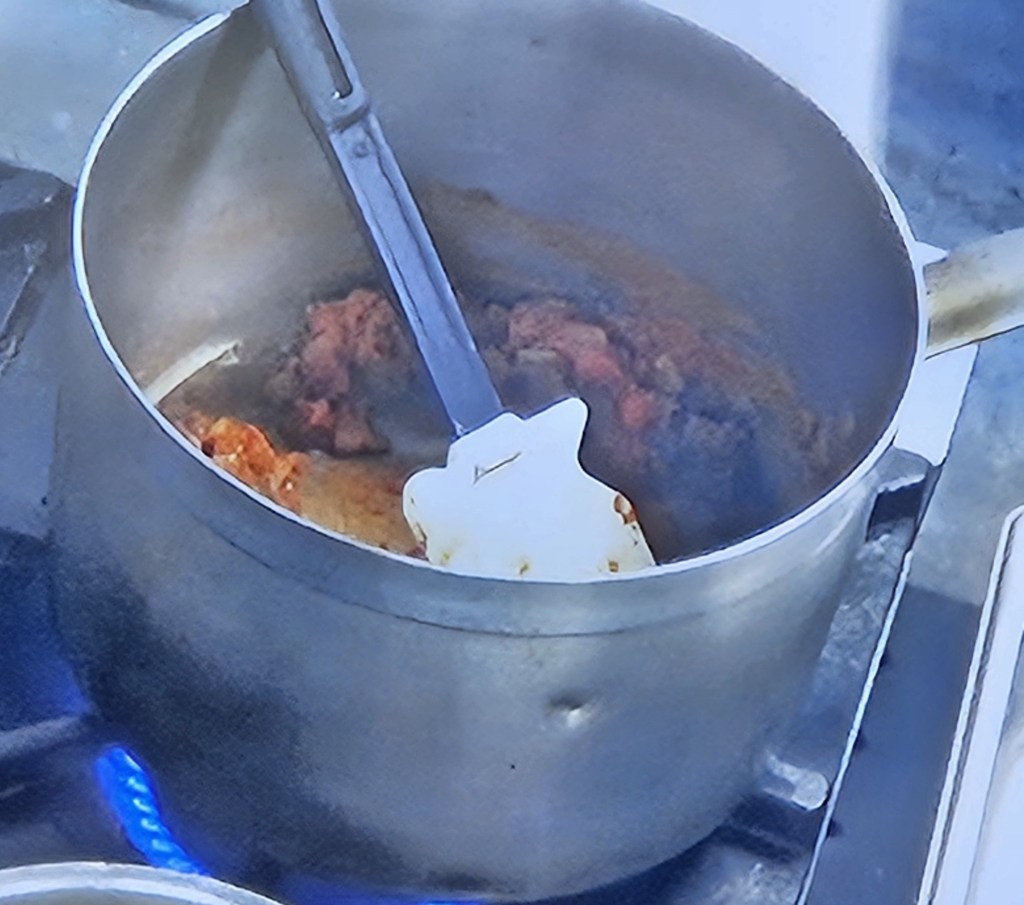

Espagnole uses a darker brown roux, more vegetables, and adds some tomato for a rich beefy taste. The roux and vegetables are cooked together to reach caramelization, adding a delicious sweet later tot he flavor of the sauce. Tomato is a simple tomato base with light herbs, like (but not identical to) a restrained marinara. As someone who likes the bold taste of a “red sauce” (shout out to Long Island Italians), I was surprised at the nuance of flavor in a seemingly mild liquid.

The kitchen lab is starting to get tight at this point. Our stoves have six burners a piece, and students compete for space. We have always been responsible for washing our own dishes, but sauce week has driven home how important tidiness and cleaning are. Chef demands we “work clean” and plan ahead. Juggling these tasks is a very real part of our education. No coworker in a restaurant is going to give up their space because you fell short.

The pressure is also mounting with items like these sauces, as we actually save most of them for future use. Messing up a sauce today means shorting yourself later. And rushing a sauce means a lackluster base for future work. Part of the reason we were able to achieve such rich flavors with humble ingredients is simply time on the stove. There’s no secret magical ingredient that suddenly imparts the complexity brought by mere heat and time. More life lessons that I seem to need to hear over and over again…