“I tried to explain to Nami how much it meant to me to share food with her, to hear these stories. How I’d been trying to reconnect with memories of my mother through food…but I couldn’t find the right words and the sentences were too long and complicated for any translation app, so I quit halfway through and just reached for her hand and the two of us went on slurping the cold noodles from that tart, icy beef broth.” – Michelle Zauner

Michelle Zauner’s Crying in HMart is a love letter to grief, her mother, and ultimately food. The quote above describes eating naengmyeon with her aunt in Korea after the passing of her mother. I envy my fellow students who have stories of cooking at a young age with parents or grandparents. I envision the smells floating around them like a cloud as they work together to build a delicious meal. Laughter amid the sounds of thunking knives against wood and bubbling liquid. Maybe the occasional curse word as recipes come together or not. Lessons learned and handed down like heirloom jewelry and treasured maybe even more. A piece of jewelry is static. Food cooked together is living connection that transcends time and space. When you cook a recipe you inherited from a loved one, they are with you every time you make it.

My childhood relationships with food and cooking were not like that. My parents divorced when I was very young, so I grew up in two diametrically opposed and equally unhealthy kitchens. In my mother’s house, food was a reward for labor. If you were hungry, you ate what was placed in front of you, regardless of temperature, texture, flavor, or personal preference. It was also intimately linked with punishment. My sister and I were often sent to bed without supper or forced to finish our plates to prove a point. I remember complaining about the texture of some strange mix of canned vegetables (corn with…tiny bell peppers? Some odd early 90’s “medley”) and being locked in the pantry until I finished an entire bowl of it.

My father’s house balanced extreme over-indulgence with scarcity. A young single father who grew up as a spoiled only child, he had no real caretaking experience for young girls. We ate when he was hungry and at places he liked: fast food joints, late night diners, and all-you-can-eat buffets. After such strict restriction at my mother’s house, my sister and I went nuts during our time with him. We gorged ourselves on everything we couldn’t readily identify on menus or icy steel bins, from shrimp cocktails to patty melts to Caesar salads. We often made ourselves sick. He also would eat only 2 meals a day, skipping breakfast for massive piles of food at mealtimes. He did not cook and kept no food in the house, so whatever my sister and I could get when we ate out was it for the day. When I got older and started carrying around a backpack, we snuck rolls and candy bars to snack on when he wasn’t looking.

Because of these wild vacillations, I thought I was a picky eater (or just “wasn’t hungry”) until I met my partner. They introduced me to proper cooking techniques, seasoning (SALT!), and the flavors behind a variety of common meals. During our early years of dating, I found myself repeatedly thinking, “I didn’t think [insert food here] could taste like this!” My partner introduced me to all of my current favorite foods: olives, mushrooms, fish in a variety of forms, and HEAT! Chiles, wasabi, horseradish, anything bringing warmth to my palate and soul, is because of them. Truly, part of the reason I love food and cooking and was inspired to go to culinary school is due to their influence (Thank you, my love!)

Which brings me to soup. I was dreading this week, especially in the summer heat. Growing up, soup came from a can, fell into a bowl, and hit the microwave before being served at nuclear temperatures. Maybe if you were lucky, it came with a piece of white bread for dipping. I learned so much from Sauce Week that I was willing to suspend disbelief that soups could (and would) blow my mind.

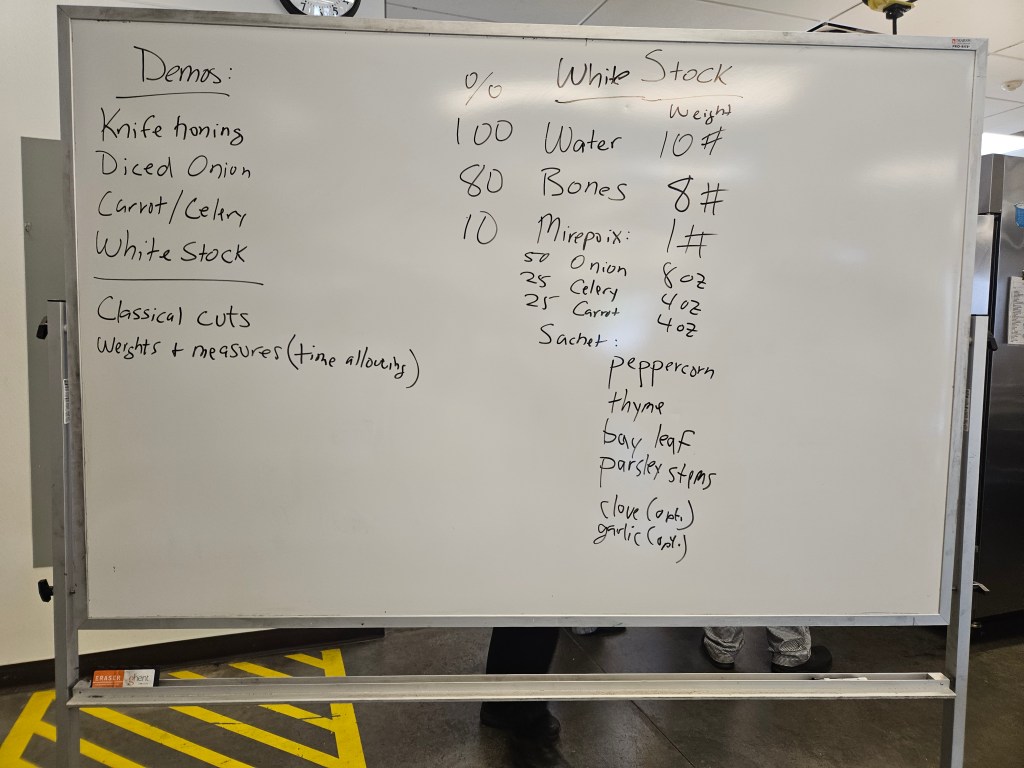

First, more practice with knife cuts (of course, of course!) as we prepared a clear broth with vegetables. The purpose of this dish is to have a flavorful broth that doesn’t obscure the delicate cuts of the vegetables. Chef asked us for simple brunoise (1/8 inch cubes) but the recipes in my textbook highlighted even fancier cuts that made the vegetables look like gemstones in the dazzling liquid. Chef recommended fewer solids and more liquid, to really highlight the broth, but I loved the little bits so much, I just had to pile them into the cup. The result was a simple but elegant little bite, inviting and warm.

I had been dreading cream soups. On paper, nothing seemed more revolting. I had experimented with them in the past at home and felt truly baffled. It turns out, like most fine French cuisine, the answer is butter, cream, and attention. I had the chance to use a Vitamix to puree my broccoli and understood the hype of the pricey machines. My Cream of Broccoli came out smooth to the taste, with lovely little speckles. Garnished with a lightly blanched floret, and while I may not be ordering a cream soup for dinner any time soon, I was convinced of the appeal.

We also tackled a Pea Puree with Mint Cream. Yes, I whipped the cream by hand. Yes, my quenelle (the football shape of cold cream that should be smooth) is terrible. I brought myself to care about cream of broccoli, and even pea puree, but hand-whipped mint cream was out of my reach. My hands were shaking by the end of class when I prepped the cream.

Traditional Minestrone felt much more like home. The recipe differed quite a bit from the one I made, but I was excited to see what would come of it. This version was delicate and light, but I craved the pile of garlic I usually added. The discreet little minces that our class recipe called for seemed to evaporate the moment it hit the liquid.

Which brings me to the real triumph: Green Chile Stew. This local hero of a dish is one of the greatest of the greatest. Pork, onions, tomatoes, potatoes, and heaps of hot green chile.

We cooked the stew for several hours, over the course of two days. Using the blast chiller, we cooled our work from Day One, so it would be ready for Day Two.