“There is nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.” – Octavia Butler

During one of the first days of class, Chef declared that it would be highly unlikely, and in fact probably impossible, that one of us (or any other culinary student) would create a brand-new dish. He explained that people have been eating for as long as there have been…well, people. And the ways that we approach cooking is actually highly standardized. I remember being taken aback, and thought his words were discouraging, especially coming from a teacher. Respectfully, how the hell would he know? But I’ve thought about his words, and what was more likely his true meaning (autists like me can often take phrases way too literally, as I was doing in this case). What he was really getting at was not short-changing our creative potential. Rather, the world of cooking follows a series of basic rules (altered slightly based on history and culture) and branches out in certain predictable pathways. I understood this concept more as we worked on sauces. It wasn’t that every single sauce that could ever be made has been made. It’s more about pulling back and seeing sauce-making (and food in general) as more about methods and approaches.

This perspective shift is one of the greatest changes for me as a home cook and future…somehow…professional…food something. Instead of seeing dishes as unique pairings, they are really more like formulaic composites. For example, “rice pilaf” is, according to my cooking textbook, a rice dish in which carrots, celery, and onion are simmered in butter. The rice is then toasted in the vegetable-butter mixture. Stock is added. The rice, carrots, celery, onions, butter, and stock are then cooked in an oven until the rice is tender. If we instead look at “pilaf” as a general method instead of a particular dish, then we have the following: vegetable + fat + grain + liquid + simmering heat (stove top) + radiant heat (oven) = pilaf. Rice can be swapped for bulgur, carrots for parsnips, butter for oil, and so on. Chef’s point was likely not that every single version of every possible pilaf in every universe has been named. Rather, the systems and practices in place mean that cooking is as much a science as an art. Perhaps more so.

As I mentioned in my previous post, even the most complex sauces are really just liquid + thickening agent + seasonings. And the results of those can just be repeated into “new” sauces indefinitely, with more liquid, more thickening agents, and more seasoning. The patterns are sort of beautiful, like when the veins of flower petals or plant leaves seem so random until you pull back and see the repetitions in their creation.

Okay, onto Hollandaise. The most brutal, unforgiving, and generally unsatisfying project in class so far. We did some other things that day which turned out quite well. I won’t be discussing those. I want to rant about Hollandaise.

I knew things were going to be tough when Chef said no professional makes Hollandaise like this any more, to which a starry-eyed fellow student asked: “Chef, is there then an increase in quality if we prepare it by hand?” Chef answered, “No. It’s almost always worse. Most professional cooks use blenders, which are much more dependable and accurate.” Student: “Then why do we do it this way?” Chef: “To punish Culinary Arts students.”

-_-

Hollandaise. Here is how Chef made his:

- Make an au sec (“almost dry”) reduction of vinegar, crushed peppercorns, and salt. Strain.

- Make a hot-water bath by simmering water in a pot. Cover with a towel and place a bowl on top

- Beat egg yolks and reduction until ribbons appear.

- Slowly add warmed clarified butter and continue beating.

- Thin with lemon juice, if needed.

- Add salt as needed and a pinch of cayenne.

- Get the mixture up to 135 degrees. Serve and enjoy.

Here is how I made my Hollandaise:

- Ask Chef if we have to actually hand-crush the peppercorns. (Chef says yes). Make an au sec (“almost dry”) reduction of vinegar, crushed peppercorns, and salt. Strain.

- Make a hot-water bath by staring at your water for what feels like 45 minutes. Nothing will happen. Walk away for three seconds. Come back to a roaring boil. Reduce heat and wait another 8 days for the water to come down to a simmer.

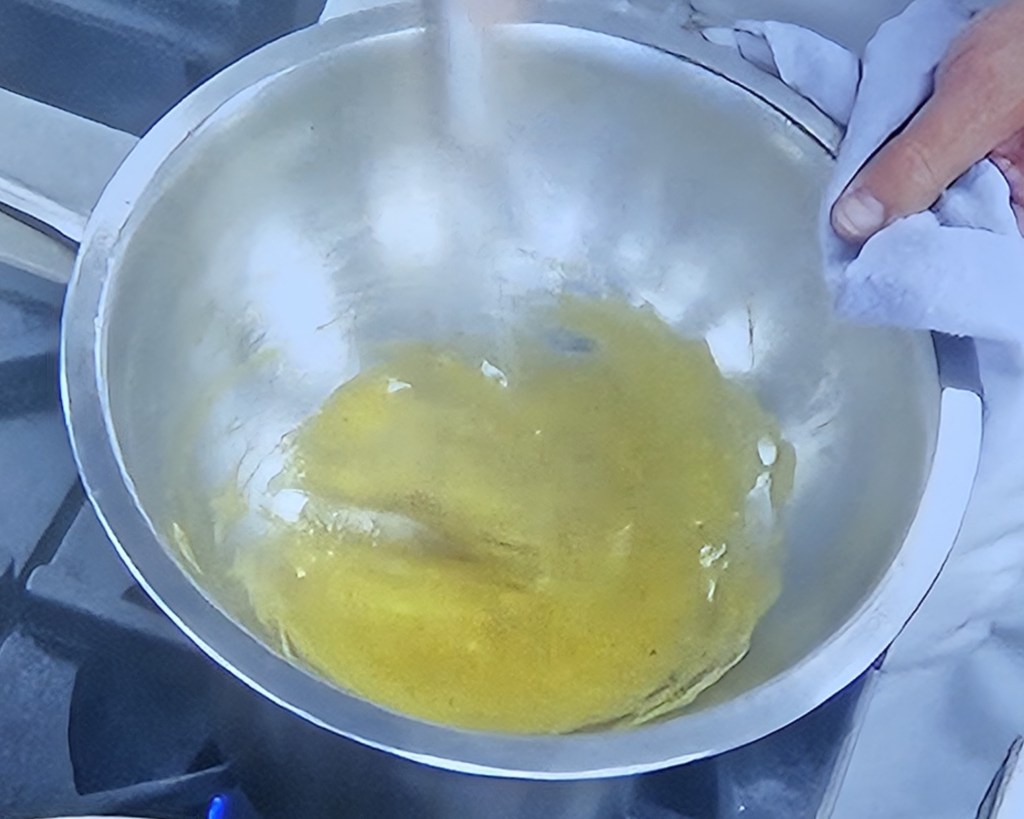

- Cover with a towel. The towel will immediately fall into the pot of water right when Chef is looking. Place a bowl on top.

- Beat egg yolks and reduction until ribbons appear. Forget what “ribbons” means and/or looks like.

- Beat forever.

- Sweat in actual rivulets. Keep beating.

- Okay, maybe that’s a ribbon.

- Slowly add warmed clarified butter and continue beating.

- Realize that your towel is on fire. Smack it with your whisk to get it out because you can never stop beating.

- Thin with lemon juice, if needed. Accidentally pour it all in because your hands are shaking because your arm muscles are goo.

- At this point, it will thicken and actually look sort of correct and beautiful. This is a fleeting moment that you should treasure.

- Add salt as needed and a pinch of cayenne, which you forgot to do earlier.

- Beat forever. The pain will never stop.

- Listen to the screams of agony around you as your classmates ruin their Hollandaise one by one.

- Get the mixture to 115 degrees and feel confident. Try to poison Chef with it, who then reminds you it needs to get to 135 before being served.

- Die inside.

- Your uniform is wet. You are wet. The pain is everywhere. Never stop beating.

- The mixture reaches 130 degrees and breaks.

- Scream.

- Start all over again.

The best part is when you taste the Hollandaise that you bled, sweat, and cried over and you realize…you don’t even like it.